New Title IX Rules Proposed

The PCA’s commitment to serving survivors of interpersonal violence and their loved ones is not in any way altered by the proposed guidance released by Secretary DeVos. We will continue to serve the students, faculty, and staff of the Auraria and Anschutz campuses with compassion, empathy, and conviction.

Read moreWhat Does The Kavanaugh Confirmation Mean?

The morning after the nation witnessed over four hours of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s grueling, emotional, and intimate testimony detailing the sexual assault she experienced in high school, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IO) spoke at a Senate Judiciary Committee meeting. Dr. Ford alleged Judge Brett Kavanaugh, a Supreme Court Nominee, was the perpetrator. Senator Grassley lamented that the burden of proof was on Dr. Ford, not Judge Kavanaugh, and asserted she did not meet it. Despite protest from citizens and legislators alike, Senator Grassley went ahead with a vote on Judge Kavanaugh’s nomination in the Senate Judiciary Committee, sending it to the Senate floor for a confirmation vote.

During Dr. Ford’s testimony, Senator Grassley, along with other Senate Judiciary Republicans, yielded their time to question Dr. Ford to Prosecutor Rachel Mitchell. They sat quietly, listening, as Dr. Ford spoke. When Judge Kavanaugh began his testimony, emotions ran high. Judge Kavanaugh raised his voice in anger and frustration, sometimes talking back and acting combatively toward female Democratic Senators questioning him. When it was time to question Kavanaugh, Republicans ignored Prosecutor Mitchell and spoke for themselves, often lamenting on the hardship Kavanaugh has faced since allegations of sexual misconduct were made public. One Senator went so far as the describe Kavanaugh’s experience as hell. Dr. Ford was barely mentioned.

What does this tell us about our culture? What does it mean, if for the purposes of a job interview, a sexual assault survivor comes forward about an applicant’s misconduct, and the applicant’s future employer conveys it is on the survivor to meet the criminal standard of the burden of proof? Are we a society that largely believes survivors or actively disbelieves and blames them?

There are many reasons survivors of interpersonal violence, including sexual violence, relationship violence, and stalking, do not come forward with their stories or report their experiences to law enforcement. One of the biggest reasons is fear of not being believed. It’s a reasonable fear. One study found “victims may be better off receiving no support at all than receiving reactions they consider to be hurtful” (Campbell et al, 2001). There are many reasons that explain why 69% of sexual assaults go unreported, including fear of retaliation and fear of not being taken seriously by police (Department of Justice, 2013). In the aftermath of victimblaming comments by government officials, #WhyIDidntReport trended on Twitter. The hashtag explored the countless reasons survivors of violence, like Dr. Ford, choose not to report the violence enacted upon them.

When Dr. Ford came forward because the media learned her identity, she had many resources at her disposal that most survivors do not. Dr. Ford has familial wealth, a doctorate, an established career in education and research, and many forms of identity-based privilege. When questioned during the Senate hearings, Dr. Ford was calm, composed, differential, accommodating, and all around likeable. Public reaction to Dr. Ford was very different than the reaction to Anita Hill, a Black woman and law professor who accused Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment during his Supreme Court confirmation hearings. Professor Hill was smeared as mentally unstable, promiscuous, and attention seeking.

Unlike Dr. Ford, Judge Kavanaugh displayed heightened emotions and outrage during his testimony. He was applauded by his supporters for it. It was very different response to a public display of anger than that of Serena Williams outrage at the US Open in early September. What does this tell us about who is “believable” and who is able to express emotion without consequence in our society? Why are some survivors believed or placated while others are not?

At the Phoenix Center, we know multiple systems of oppression impact how violence is perpetrated and experienced. We also know the three most important words that can be said to a survivor are, “We believe you.” At the Phoenix Center, we believe you, always.

Campbell, R., Ahrens, C.E., Sefl, T., Wasco, S.M., & Barnes, H.E. (2001). Social reactions to rape victims: Healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence and Victims, 16, 287-302 (quote on p. 300).

Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994-2010 (2013).

Official PCA Statement of Solidarity

THE PHOENIX CENTER AT AURARIA | ANSCHUTZ

As the nation has again turned its attention to the issue of sexual violence, the Phoenix Center at Auraria | Anschutz (PCA) has observed a mix of responses to the allegations being brought forth against Judge Kavanaugh. As the interpersonal violence resource center serving our four campus communities, the PCA wishes to make its position on some of the major issues currently present in the media stratosphere clear:

The PCA holds the position of believing all survivors. We believe every person who engages with us regardless of age, gender identity or expression, race, ethnicity, country of origin, immigration status, sexual orientation, primary language, religion, military or veteran status, or socioeconomic status. We believe every person regardless of when the traumatic event happened in relation to their coming to us. We believe every person regardless of how much they do or do not remember about their trauma. We believe every person regardless of how their trauma presents itself. We believe that every person and every person’s experience is valid and we continue to work towards a world in which this belief does not need to be stated, but is accurately assumed of all citizens of humanity.

We acknowledge that there are many concerned about the issue of false reporting. According to a number of large-scale, international research studies[i],[ii],[iii],[iv], the rate of false reporting of sexual assault sits at 2% - 8%. At the most conservative, this means that 92% of all people who have the ability to come forward and speak about the crimes committed against them are telling the absolute truth. As such, research supports that all people start by believing the stories they are hearing about sexual assault. This is not to say that no one ever makes false claims. However, the harm that folx enact by starting from a position of skepticism and demanding to be convinced (rather than starting from a position of belief) is greater by far than the harm experienced by feeling betrayed in the small amount of cases where someone is not being truthful. A study conducted by Dr. Rebecca Campbell from Michigan State University in fact found that “Victims may be better off receiving no support at all than receiving reactions they consider to be hurtful,”[v] and, further, that receiving hurtful reactions hampers many survivors from feeling comfortable reporting to law enforcement ever if at all.

Studies about the recollection of traumatic memory have made clear that it is nearly impossible for a person to recall traumatic memory with perfect logical or linear certainty due to normal, neurobiological processes. The time which has elapsed between a traumatic event occurring and a traumatic event being recalled does not have any bearing on the validity of the report.

There are many valid reasons that a person may not choose to come forward about a traumatic event. In fact, studies show that only 30% of rapists are ever reported to the police and only .6% will ever see the inside of a jail cell[vi]. The PCA does not stand in judgment of a person’s choice about when or even if they would like to bring to light their experiences. The PCA supports survivors of interpersonal violence – all survivors – at all times, regardless of whether or not they choose to engage law enforcement or campus authorities.

The experience of being triggered or emotionally impacted does not negate any survivor’s progress on their own healing journey. The experience of being triggered or emotionally impacted is not a sign of weakness. These experiences are signs of being humans who have been impacted by trauma. They are normal and they are valid.

Finally, the PCA would like to remind the campus community that we are available to assist survivors of interpersonal violence as well as folx who are supporting survivors of interpersonal violence during Auraria drop-in hours (8am – 5pm), via our 24/7 helpline (303-556-2255), or by appointments made through our office (303-315-7250 - Auraria, or 303-724-9120 - Anschutz). The PCA is a free & confidential resource for students, faculty, and staff affiliated with the Auraria and Anschutz campuses. The PCA is available to provide short-term emotional or crisis support, advocacy, and referrals for other resources. The campus counseling centers are also available to our community. Their respective information can be found below:

Community College of Denver Counseling Center

CU Anschutz Campus Health Center & Counseling Services

CU Anschutz Department of Psychiatry

Together, we believe that we can continue to create and maintain a campus community where survivors are believed and supported. In this way, we can all contribute to a global society in which the same is true.

In Solidarity,

The PCA

[i] End Violence Against Women International: Making a Difference Project, 2009

[ii] Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa, & Cote, 2010

[iii] Kelly, Lovett, & Regan, 2005

[vi] Department of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 2010-2014 (2015)

Relationship Red Flags

Last Friday, PCA staff, students, and campus volunteers worked for two hours to install our annual Red Flag Campaign on the lawn outside of the Plaza building. Each year, the PCA has installed this eye-catching display, but what for?

The Red Flag Campaign is a national campaign which was created by and for college campuses with the guidance of the Virginia Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Alliance. 1 in 4 college-aged folx experience relationship violence and the purpose of the red flag campaign is to raise awareness around “red flags” in unhealthy and abusive relationships. This way friends, family, and loved ones can be active bystanders when they see something happening in someone’s relationship that isn’t right or isn’t healthy. So, what are some of those red flags? Here are 7.

Jealousy

There’s this weird idea in our culture that jealousy = love and that just simply isn’t true. If a partner is “over-protective”, jealous, or always on their partner’s case about who they are spending time with, when, how, and why, this isn’t about caring about the person: it’s about controlling who they spend their time with. Relationship violence is a constant cycle of a perpetrator working to obtain power & control and jealousy is one emotionally abusive way that control is established and maintained. It doesn’t help that our culture laughs it off as cute or proof of someone’s devotion. (Not to mention that telling your partner to shut up in any kind of seriousness can also be considered verbal abuse)

2. Emotional Abuse

Calling your partner cutesy names Is par for some relationships, but calling your partner names because you are mad at them or names based on things you know they feel badly about is not ok. Like, for instance, calling a partner “Piggy Pig” when they feel insecure about their weight? Not cool.

3. Victim Blaming

This may be a cringey ad from the 1950s, but there is nothing that makes a person harming their partner in any way ok, even not store-testing coffee (whatever that is). Remember what I said about abuse being a cycle of power & control? A common tactic of abusive partners is to blame their poor and abusive behavior on the actions of the person they harmed. Things like “If you had only had dinner ready when I came home, I wouldn’t have had to yell at you” or “If you’d only given me your full paycheck when I asked for it, I wouldn’t have had to punch the wall” are common victim blaming sentiments in an abusive relationship.

4. Stalking

Tell me if you can find something creepier to say to someone that “every breath you take, every move you make, i’ll be watching you.” Decidedly NOT ROMANTIC. When someone lays a clear boundary about how they wish to be contacted - or NOT - and the person they’ve laid the boundary with doesn’t respect it, this is stalking. We often brush stalking off as cute or sweet (as in the whole TV show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” but it’s anything but. Stalking behavior can be anything from physically following another person to sending them unwanted messages to showing up places where they have no other reason to be to sending unwanted gifts. Stalking is serious, ya’ll. If it’s a safe option for you, call the real police if anyone ever says any of these lyrics for real.

5. Physical abuse

Physical abuse is often the first thing people think of when we begin discussing relationship violence. It’s the most obvious outward sign that we as a society have agreed indicates maltreatment. There is nothing that makes physical abuse ok, whether it results in bruises or abrasions others can see or not. Often, people experiencing physical abuse will take pains to hide the evidence from others (for a series of very valid reasons). For instance, if you notice your friend or loved one wearing long sleeves when it’s 90 out, maybe ask them about it. It could be laundry day, or it could be something else.

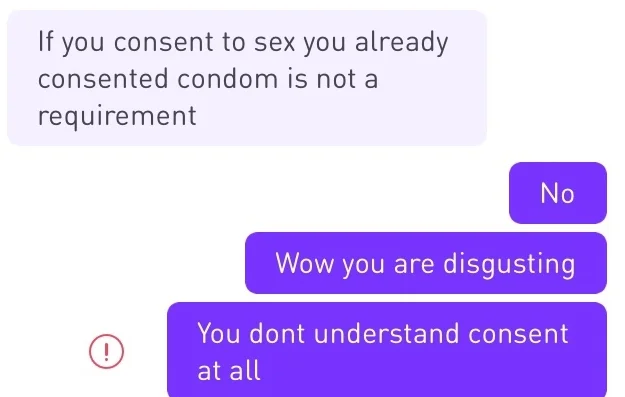

6. Sexual Abuse

There still exists an idea that sexual abuse is impossible within the confines of a romantic or intimate relationship. It wasn’t until 1993 in fact that “marital rape” actually became illegal in all 50 states and some states still have laws on the books which make it difficult for sexual violence within a relationship to be prosecuted. Regardless of someone’s official relationship status, sex is never a guaranteed commodity. A person - solely by virtue of being a person - has the right to determine who touches their body and how at all times. Sexual violence isn’t just forced intercourse either. As illustrated by the text above, the fairly new trend of “stealthing” (removing a barrier method without a sex partner’s knowledge after they agreed to have sex with the barrier method) is also sexual violence. As is coercion, performing sexual acts while someone is unconscious (sleeping or intoxicated), forcing someone to perform sex acts on another person, or any nonconsensual sexual activity. Just because you buy someone dinner or pay half the rent does NOT mean they owe you sex.

7. Isolation

Maybe it’s telling that I don’t have an interesting listicle image for this one. Another common power & control tactic is isolating the other partner from their family and friends. As with many other power & control tactics, it can start out very subtle with something like “I just don’t like you hanging out with that person” or “I just miss you so much when you’re not with me” and these, on their own, may not be red flags. However, when one person becomes every person but the partner and someone can look back and realize that they haven’t talked to anyone but their partner in a shocking amount of time, this is when red flags should go up. If your friend or loved one drops off the face of the earth, don’t just assume they’re lost in a haze of new relationship bliss, keep in touch!

These are only a few of the many signs of relationship violence. Bottom line: If something seems not ok to you, it probably isn’t. Don’t fall into the trap of assuming it’s none of your business, if your loved one seems in trouble step up and ask if they’re ok!

Not sure how to do that? Call or stop by the PCA any time!

In the News: Rape Culture

On August 31, as the world gathered to honor the incredible life of music legend Aretha Franklin, rape culture made sure to also demonstrate its attendance. It should not come as any surprise that rape culture was present in this most sacred of places. Following the flood of #MeToo disclosures last October and ongoing, it should be old news that sexual harassment will occur in every facet of our lives, that no place is actually sacred.

If you’ve been following the news, you’ll know that following Ariana Grande’s performance of Aretha’s classic “You Make Me Feel (Like a Natural Woman)”, Bishop Charles Ellis III groped her breast while making a racial slur about her name. At this moment, as Bishop Ellis sexually assaulted a person on live TV and in front of hundreds of mourners, rape culture began to unfurl in three distinct ways.

First, it showed up in the utterly pointless coverage of the length of her dress. A sexual assault had occurred, and the (social) media stratosphere was more concerned with the length of her dress. So obsessed is our culture with policing people’s bodies (especially those coded as feminine), that coverage of her actual performance was nonexistent in the onslaught of criticism for the length of her dress. This then became inextricably linked to the assault Bishop Ellis chose to commit against her when gospel Reverend R.L. Kemp tweeted: “He was wrong. Arianna’s dress was to [sic] short. Women know just what they are doing when they wear a short mini black dress. She got what she deserve [sic], attention…and then some. The Bishop got carried away and did what most of the guys on the platform and in the audience wanted to do”. As our Violence Prevention Educators have taken to saying around the office: there’s a lot to unpack here.

Briefly, the Reverend begins his post with the statement that the Bishop was wrong but then undermines this point by defending the actions of the Bishop, stating Grande asked to be assaulted by wearing a piece of clothing, dismissing assault as attention, and calling forth the stale ideologies of Saint Augustine and original sin. This is one example of a victim-blaming framework which arrives as if on cue each time another story of sexual harassment and assault is spread across social media.

Second, it showed up in coverage applauding the actions of the bishop. Mike Colter, headliner for Netflix’s series Luke Cage, tweeted “Now THIS is how you shoot your shot! Zero FCKS!!! 😭 😭 😭” . This builds on the idea Reverend Kemp proposed in his tweet: that every man wanted to do the same thing and that wanting to do so is grounds to do so with or without the consent of the person being objectified. Colter identifies here the blatant nature with which the Bishop undertook his assault. “Zero FCKS,” he says before laughing about it. This is rape culture apologism; he identifies the behavior as abnormal and then lifts it up as an acceptable norm. He has since issued an “apology”.

This brings us to the third blatant appearance of rape culture, “apologies” and their media coverage. Google Bishop Ellis’ crime and you will see numerous articles with the headline “Bishop apologizes…” but when you read the text of his apology, no true apology appears. He discusses his wholesome intentions, links them to the church being about love, and then says, “Maybe I crossed the border”. At no point in his apology, even when he seems to walk back the validity of his intentions, does he state definitively that his actions were wrong and inappropriate. He places the full blame of the incident on Grande’s interpretation of the event. His intent and her interpretation are null and void when confronted with the clear fact that Bishop Ellis groped a person’s breast without their consent. This is arguably the most insidious element of rape culture now gripping our nation: the fake apology. Mike Colter did the same thing in his “apology”, calling on his innocuous intentions and laying the blame on people taking it wrong. We saw the same with Kevin Spacey, Aziz Ansari, and to a certain degree Louis C.K. These. Are. Not. Apologies. They are platitudes designed to look and sound like apologies while still avoiding any responsibility.

As the nation becomes increasingly aware of the reach of sexual violence and gender discrimination, the PCA and others like us are repeatedly asked how we as a nation will heal and move forward. The answer is simple: we will begin to heal and move forward when perpetrators of violence and discrimination are held truly responsible for their actions. Until we refuse to accept platitudes dressed as apologies and demand social accountability, the cycle will continue. The power of the #metoo movement is that of increased awareness. Now armed with awareness, we are charged to end it.

To learn more about how the PCA is working to end it, see https://www.thepca.org/prevention-education/ or follow us on social media!

The Distance Between Summer and School

With August coming to a close and summer retreating in the distance, it’s time to trade in your summer reads for textbooks, pack your favorite undies/socks, and prepare for the start of a new semester at college. For some of you, the end of summer does not just mean saying dramatic goodbyes to your dog or bracing yourself for dining hall food, it also means moving away from your partner. Maybe you’re about to start your freshman year at college, and your partner is still in high school, or you’re still in college and they’re preparing to move away for graduate school, or one of you is going abroad. Long distance relationships in college come in all shapes and sizes, and start for any number of reasons, but the one characteristic that should be consistent in every long-distance relationship is healthiness. An unhealthy long-distance relationship can be incredibly damaging to both partners and has the potential to escalate into interpersonal violence.

They, the powers that be, say the key to any long-distance relationship is communication, but it is always important to realize when healthy communication has taken a turn for the worse. It’s natural for you and your partner to miss each other, but behaviors such as sending you coercive text messages, getting upset when you don’t respond to them immediately, or overwhelming you with phone calls are not a healthy piece of a partnership. Keeping in touch with a long-distance partner should be something you want to do, and you should never feel intimidated into talking to them, or obligated when engaging in sexual activities like sending them nudes or sexting. Depending on the couple, keeping in very close contact can be a mutually agreed upon boundary, but if the sound of your phone going off makes your heart race or the idea of missing a call from your partner gives you anxiety, it is time to take a second look at your relationship.

College is about academic achievment, but it’s also about enjoying yourself. If your partner is preventing that, your relationship may not be healthy. Everyone in college has a different idea of fun. For some people, the ideal college experience is a four-year long alcohol induced haze; for others, it’s all about quiet nights in with their friends. Different long-distance couples set boundaries that work for them about how they behave when they are apart. Be careful not to confuse boundaries with control. Your partner should not be doing things like manipulating you into feeling guilty about having fun without them, forcing you to Snapchat them constantly so they know your exact location, or stopping you from having friends that they do not know. Jealousy, insecurity, and heightened emotions are natural in long-distance relationships, but they should not consume you or your partner to the point where either of you is no longer treating the other with respect and trust.

Long-distance relationships aren’t for everyone, and they most certainly aren’t easy, but for them to work it is so important that both people are committed to maintaining a healthy relationship. The key to any relationship is communication, and in the beginning of the long-distance relationship, it is especially important to be honest and establish boundaries. For example, you and your partner could decide, “when one of us is jealous, we will address it calmly, with a clear head, and the other person will try not to be dismissive” or, “when we are lonely, we will choose a book to read together in order to feel more connected.” Every couple has their own way of navigating a long-distance relationship, and every person has his or her own way of dealing with the emotionally-charged situations that can often surround relationships like this. At the end of the day, your gut will tell you if you are in a bad situation, and you shouldn’t ignore it. Don’t disregard red flags. Even if your partner is not physically present, it does not mean the potential for an abusive situation is gone. As you start the new semester, remember that prioritizing your relationship is important, but so is taking care of yourself.

If you or a loved one is a survivor of interpersonal violence and are looking for support, advocacy, or education surrounding your experiences, please visit the Phoenix Center at Auraria | Anschutz for additional resources. We are a confidential, trauma-informed center dedicated to supporting your journey. Feel free to stop by Tivoli 259 or send us an email at info@thepca.org!

Tendrils of Rape Culture

I’ve been having many discussions lately regarding the underpinnings of rape culture and the seemingly invisible tendrils it has woven into American culture so it was on my mind when I was scrolling Facebook this afternoon while waiting for my friend’s husky to do his business.

A while ago, I read an article which cited Mohadesa Najumi’s definition from her article on The Feminist Wire:

“Rape culture … is the production and maintenance of an environment where sexual assault is so normative that people ultimately believe that rape is inevitable.”

What Najumin speaks of here is the concept that there are things in our society that are not rape but are abusive, or contributive to abuse, which we accept as cute, funny, and desirable. These things may seem harmless on their own, but placed into the larger spectrum of Rape Culture they become concerning.

Take, for example, rape-y songs and song lyrics. Robin Thicke’s 2013 song “Blurred Lines” was a summer smash hit at the time and caused quite an uproar in some circles with lyrics like “I know you want it” accompanying inexplicably plastic-clad or naked (in the “unrated” version which is still somehow available on YouTube) women. At no point in time in the song did a woman pipe up and say “yes, I do” or “I want sex” indicating she was both consenting and consenting explicitly to sex as opposed to some ubiquitous “it”.

There was a moment that summer when I found myself in a car with a number of victim advocates and “Blurred Lines” came on the radio. The driver turned up the song and I asked if he had heard the hubbub over the lyrics. He replied that he hadn’t so I summed it up for him. The carful of people nodded along with my summary before someone woefully exclaimed the largest issue with the song: “Oh, but it’s so catchy!” Herein lies the issue with this song, advertisements, and so-called “off-color” jokes: society is generally willing to overlook rape-y messaging when it’s packaged in a catchy tune, tagline, or image.

We tell ourselves that lyricists and artists don’t really mean for their lyrics or art to be rape-y. We choose to believe that the person saying things like “I’d tap that” and staring as an attractive person walks past is a nice person and, thus, would obviously obtain consent. We perceive pictures like the above as cute and innocent because we want to believe they don’t convey a nonconsensual, sexist experience. We choose ignorance because it’s easier. We choose ignorance because the world is so full of negativity that we don’t want to see it anywhere it isn’t explicit. It’s a self-protective choice and, yet, it only contributes to a world in which more violence is perpetuated.

How do we choose differently? The answer is not to always assume the worst over the best or automatically condemn anything questionable. Neither is it to loudly shout down people who engage in or create the content. I’m not even suggesting that you delete all your music and social media. I’m suggesting we stop blindly nodding our heads to catchy tunes, shaking them as we scroll passed content that walks the line of acceptability, ask the questions with curiosity, and explore the answers.

Megan Alpert

TIME FOR THE TALK: LGBTQ STUDENTS, INTERPERSONAL, AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE

When are we going to talk about violence in the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) community?

By talk, I mean one of those deep around the fire conversations, not a ran into an acquaintance at the grocery store conversation. A real conversation. A conversation that has meaning, like one you replay over and over, one that is unfinished and continuous.

When I say violence, not only do I mean violence enacted upon us in the queer community, such as state violence, physical violence, emotional and spiritual violence, but violence we enact upon each other.

In recent years, higher education has begun to pay attention to interpersonal violence (IPV) and sexual violence. Unfortunately, the narrative of who experiences violence has gone largely unchallenged. White, cisgender, straight, middle class women without mental illness or disabilities are often centered in violence prevention and response.

From the beginning, exclusion of LGBTQ folks from the anti-violence movement has been common place. The Battered Women’s Movement in the 1970s centered sexism and male privilege, but failed to deconstruct intersections with homophobia and transphobia (NCAVP, 2014). The narrative of cisgender men as perpetrators and cisgender women as victims quickly took hold in our societal perception of violence and became institutionalized in domestic shelter policies, legislation, law enforcement response, and court systems (NCAVP, 2014). On college campuses, this narrative is often reflected in our bystander intervention programs, Title IX response, and survivor support services.

LGBTQ folks have always experienced, and continue to experience, IPV and sexual violence. In a society built on heterosexism and cissexism, our relationships and what happens in them often remain invisible. Laws utilize gendered stereotypes and language defining intimate relationships as heterosexual (Kingkade, 2015). Some states go so far as only using “he” pronouns when describing perpetrators and limiting definitions of sexual assault to nonconsensual intercourse between members of the opposite sex (Kingkade, 2015). As Shannon Perez-Darby states, “because of homophobia, transphobia, and sexism, gender becomes a much less reliable tool in queer and trans communities for evaluating who is battering and who is surviving in relationships.” (2011, p. 106). Societal systems struggle to develop different tools to serve queer and trans survivors.

According to the National Intimate Partner Violence Survey of 2010, conducted by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals have an equal or higher change of experiencing IPV and sexual violence than heterosexuals (Walters, Chen & Breiding, 2013). Almost forty four percent of lesbians, 61% of bisexual women, 26.0% of gay men, and 37% of bisexual men have experienced IPV at some point in their relationships (Walters, Chen & Breiding, 2013). Research by Julia Walker found trans and gender nonconforming folks experience IPV at higher rates than cisgender individuals (2015). These statistics are similar in our schools (Hoffman, 2016). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual high school students are three times as likely to be raped, two and a half times more likely to experience sexual dating violence, and twice as likely to experience physical dating violence than straight students (Kann et al., 2016). A survey published in 2015 by the Association of American Universities found that LGBTQ college students also experience higher rates of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and IPV than heterosexual students (Cantor et al.). Trans and gender nonconforming students were found to experience the highest rates of rape (Cantor et al., 2015).

The intersections of multiple identities significantly impact victimization rates. Data collected by the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, which consists of 16 organizations around the country providing services to survivors, indicated queer, trans, and HIV-affected people of color experienced more severe types of violence and experienced IPV at disproportionate rates (2014). Immigration status increased rates of discrimination and LGBTQ individuals under the age of 24 were found more likely to be physically and sexually assaulted in their relationships (NCAVP, 2014).

All survivors face many barriers when seeking support following IPV and sexual violence. They may not have the resources to leave abusers. Rape culture makes it possible, and even likely, survivors won’t be believed when they tell their stories and if they are, they can then be blamed for their own assault. Additionally, survivors often know the perpetrator and they can fear retaliation. Queer, trans, and nonbinary survivors face additional obstacles to these. The LGBTQ community is often close knit, and in some places small. If you know the person who abused you and is in community with you, seeking help could change relationships in the community, risking valuable support and camaraderie. You may be outed. You could lose custody of your kids because you’re not viewed as a “real” parent. Service providers can lack knowledge and cultural competency. You may be misgendered. You can face further violence by police.

Once again, intersections of identity further exacerbate the consequences of these barriers. Trans people of color are almost as six times likely to experience physical violence when interacting with law enforcement than white cisgender survivors (NCAVP, 2014; NCAVP, n.d.). Trans women are also six times to experience physical violence when interacting with police, including after an incident of IPV, compared to overall survivors (NCAVP, 2014; NCAVP, n.d.). Almost a quarter of trans folks trying to access shelters have been sexually assaulted by someone at the shelter, including staff (Grant et al., 2011). Many LGBTQ people know all too well that the people and organizations that are supposed to protect and support us far too often are the same people and organizations that hurt us.

These injustices follow LGBTQ folks to campus and affect students’ wellbeing and academic success. A 2014 study found evidence to suggest experiencing rape and sexual violence impact women’s academic success and GPA (Jordan, Combs & Smith). Unsurprisingly, research has yet to examine the relationship between LGBTQ survivorship and academic success. Regardless, are we prepared to support LGBTQ survivors’ healing journeys during their college careers?

LGBTQ survivors with all identities, backgrounds, and experiences exist – not just “out there,” but in our communities and on our campuses. Ignoring the violence the LGBTQ community faces further stigmatizes and silences our pain. Social justice isn’t only a professional competency. For some of us, it’s not only the difference between earning a degree and not, but it’s a matter of survival.

So, are we ready to have that talk now?

References

Cantor, D., Fisher, B., Chibnall, S., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Bruce, C., & Thomas, G. (2015, September 21). Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. Retrieved August 10, 2016, from https://www.aau.edu/Climate-Survey.aspx?id=16525

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Retrieved August 10, 2016, from http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf

Hoffman, J. (2016, August 11). Gay and Lesbian High School Students Report 'Heartbreaking' Levels of Violence. Retrieved August 13, 2016, from http://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/08/12/health/gay-lesbian-teenagers-violence.html

Jordan, Carol E.; Combs, Jessica L.; and Smith, Gregory T., "An Exploration of Sexual Victimization and Academic Performance Among College Women" (2014). Office for Policy Studies on Violence Against Women Publications. Paper 38. http://uknowledge.uky.edu/ipsvaw_facpub/38

Kann, L., O'Malley Olsen, E., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Zaza, S. (2016, August 12). Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12 - United States and Selected Sites, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6509a1.htm#suggestedcitation

Kingkade, T. (2015, September 9). LGBT Students Face More Sexual Harassment and Assault, And More Trouble Reporting It. Retrieved August 9, 2016, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/lgbt-students-sexual-assault_us_55a332dfe4b0ecec71bc5e6a

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). (2014). A Report From The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and HIV-Affected Intimate Partner Violence in 2013. 2014 Release Edition. Retrieved August 10, 2016, from http://www.avp.org/resources/reports

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). (n.d.). Hate Against Transgender Communities. Retrieved August 12, 2015, from http://www.avp.org/storage/documents/ncavp_transhvfactsheet.pdf

Perez-Darby, S. (2011). The Secret Joy of Accountability: Self-accountability as a Building Block for Change. In The Revolution Starts At Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities (pp. 100-113). Brooklyn, NY: South End Press.

Walker, Julia K. "Investigating Trans People's Vulnerabilities to Intimate Partner Violence/Abuse." Partner Abuse 6.1 (2015): 107-25.

Walters, M.L., Chen J., & Breiding, M.J. (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Recommended Reading:

Queering Sexual Violence: Radical Voices from Within the Anti-Violence Movement

Edited by: Jennifer Patterson

The Revolution Starts at Home

Edited by: Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Violence against Queer People: Race, Class, Gender, and the Persistence of Anti-LGBT Discrimination

By: Doug Meyer

Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law

By: Dean Spade

The Color of Violence Edited

by: INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

MythBusters: Interpersonal Violence

Anybody remember that cheesy show from the early 2000s, starring two nerdier-than-most guys, that spent roughly 48 minutes once a week debunking commonly held beliefs? Mythbuster, was it? After doing a little research, the dynamic duo of Jamie Hyneman and Adam Scott tested over 1,000 distinct myths in 217 hours, spanning 14 years, resulting in a vast amount of information about common myths and interesting phenomena.

I am going to attempt to graze the surface of myths surrounding interpersonal violence and debunk each one with a social scientific lens that highlights the misconception and re-orients the conversation around the truth. Won't you follow along?

Myth #1: INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE AFFECTS ONLY A SMALL PERCENTAGE OF THE POPULATION AND IS RARE.

FACT: National studies estimate that 3 to 4 million women are abused each year in the United States. A study conducted in 1995 found that 31% of women surveyed admitted to having been physically assaulted by a husband or boyfriend. Interpersonal violence is the leading cause of injury to women between the ages of 15 and 44 in our country, and the FBI estimates that a woman is abused every 15 seconds. Thirty percent of female homicide victims are killed by partners or ex-partners, and 1,500 women are murdered as a result of interpersonal violence each year in the United States.

Myth #2: INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE OCCURS ONLY IN POOR, UNEDUCATED, OR MARGINALIZED FAMILIES.

FACT: Studies of interpersonal violence consistently have found that violence occurs among all types of families, regardless of income, profession, region, ethnicity, educational level or race. However, the fact that lower income victims and abusers are over-represented in calls to law enforcement, domestic violence shelters, and social services may be due to a lack of other resources.

Myth #3: INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE IS USUALLY A ONE TIME, ISOLATED OCCURRENCE.

FACT: Interpersonal violence is a pattern of coercion and control that one person exerts over another. It is not just one physical attack. It includes the repeated use of a number of tactics, including intimidation, threats, economic deprivation, isolation, and psychological/sexual abuse. Physical violence is just one of these tactics. The various forms of abuse utilized by abusers help to maintain power and control over their spouses and partners. Abuse also tends to increase both in velocity and extent over a period of time.

Myth #4: SOME VICTIMS ASK FOR, PROVOKE, WANT, AND EVEN DESERVE IT.

FACT: NOBODY deserves to be beaten or abused. Victims often have to walk on eggshells and try their best to avoid another incident. The abuser CHOOSES to abuse. This myth encourages the blame-shifting from the perpetrator to the victim and avoids the stark reality that only the perpetrator is responsible for their own actions.

Myth #5: IT CAN'T BE THAT BAD, OR THEY'D LEAVE!

FACT: There are many emotional, social, spiritual, and financial hurdles to overcome before someone being abused can leave. Very often, the constant undermining of the victim's self-esteem can leave him/her with very little confidence, socially isolated, and without the normal decision-making abilities a person living free from interpersonal violence. Leaving or trying to leave will also often increase the violence or abuse, and can put the victim (and/or their children) in a position of fearing for their lives. Leaving is the ultimate threat to the abuser's power and control, and they will often do anything rather than let the victim go.

Myth #6: ABUSERS ARE ALWAYS COARSE, VIOLENT MEN AND ARE EASILY IDENTIFIABLE.

FACT: Abusers are often socially charming, generous and well-presented people (of any gender!) who hold positions of social standing. Abuse is kept for those nearest to them, to the privacy of their own homes. This Jekyll and Hyde persona of the abuser can further confuse and frighten the person being abused, as the person in private is so very different to the person everyone else sees. It can also mean that when the person being abused finally does try to tell their friends, family or acquaintances of the abuse, they are not believed, because the person they are describing simply doesn’t fit the image portrayed in public.

Myth #7: INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE DOESN'T AFFECT THE LGBTQ+ COMMUNITY.

FACT: Such myths ignore the validity of same sex relationships. Abuse is about control within a relationship and can occur within any relationship where one partner believes they have the right to control the other. Whether they are married or living together, of the same or opposite gender, have been together for a few weeks or many years really doesn’t make much difference – abuse can (and does) occur.

As you can tell, there is a lot of misinformation surrounding interpersonal violence. It's all of our duty to debunk myths, correct misinformation, and share relevant tips for supporting survivors of interpersonal violence.

If you or a loved one is a survivor of interpersonal violence and are looking for support, advocacy, or education surrounding your experiences, please visit the Phoenix Center at Auraria | Anschutz for additional resources. We are a confidential, trauma-informed center dedicated to your recovery. Feel free to stop by Tivoli 259 or send us an email at info@thepca.org!

Check out our new website!

Taylor here with a proud announcement: the NEW and improved PCA website is now live! Browse through our extensive resources, find out how to get involved with the PCA, and even schedule an appointment to speak with an advocate online.

We will be coming out with a blog each week, written by staff members, centered around IPV-related experiences and trauma-informed care tools. Stay tuned!